Tennessee Headed in a Blue Direction?

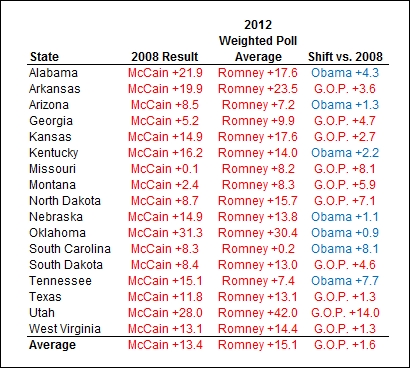

Posted: September 26, 2012 Filed under: Politics Leave a commentIs Tennessee headed toward battleground status? Ok, perhaps not, but we do know from polling that Tennessee voters are less hostile to the Democratic presidential ticket than they were four years ago, and our red-blue gap is shrinking faster than most other deeply red states. At least that’s a plausible conclusion one can draw from data compiled by Nate Silver at the The New York Times‘ FiveThirtyEight blog. Silver compared the final presidential election result in 2008 with a weighted average of current election polling in each of 18 solidly red states:

In 10 of 18 states the red grows redder — a polling lead for Mitt Romney that exceeds John McCain’s 2008 margin of victory. In the other seven, all still with Romney ahead, the redness has paled — a smaller Romney edge in polling now compared with McCain’s margin four years ago. The two states with the biggest shift blueward are South Carolina followed by Tennessee — the latter showing the red margin of advantage cut in half. And the polling data is pretty good in extent and quality: Silver’s weighted number for Tennessee relies mainly on two surveys: a YouGov poll earlier this month (finding Romney +8 among registered voters) and a Vanderbilt poll in May (Romney +7 among registered voters).

Extrapolating optimistically (if impulsively), Tennessee should be a battleground state by 2016. Not holding breath.

A version of this post appears on the Nashville Scene‘s Pith in the Wind blog.

47gate: The Myth of Progressive Taxes

Posted: September 19, 2012 Filed under: Economics, Politics Leave a commentMuch of the chatter about Mitt Romney’s now infamous half-the-country-can-go-fuck-itself video has focused on that 47 percent who in Romney’s words “are dependent upon government, who believe that they are victims…who pay no income tax.” It was this armchair analysis that inspired Romney to conclude in words that may someday grace the tombstone of his presidential bid: “my job is not to worry about those people.”

In the wake of this latest outbreak of Mittastatic cancer of the campaign voicebox much is being said about who actually comprises that 47 percent, and about Romney’s seemingly fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of tax obligation. This, in turn, predictably elicits the usual whining from the right about how wealthy taxpayers supposedly pay way more than their fair share of taxes.

At a time like this it’s worth reminding ourselves that our tax system isn’t really terribly progressive. A good way to judge is to look at the income people in particular brackets earn and compare it with the tax revenue that comes out of those same brackets. If lower income people pay a much smaller proportion of taxes compared to the proportion of income they earn, and if higher income people pay a much larger proportion of aggregate taxes than they earn, then we have a highly progressive system. So what does it actually look like?

The chart below, from The Atlantic based on data compiled by Citizens for Tax Justice, answers the question. Blue bars (income) are a bit bigger than red bars (taxes) at lower incomes, while red bars are slightly bigger than blue bars at higher incomes. In other words, very modest progressivity. Or as The Atlantic‘s economics writer Matthew O’Brien aptly puts it, “If this is Marxism, it’s very carefully disguised.”

A version of this post appears on the Nashville Scene‘s Pith in the Wind blog.

Ground Game

Posted: September 18, 2012 Filed under: Politics Leave a comment We keep hearing that the presidential election this year may come down to who has the better ground game, and perhaps it will if Mitt Romney can manage to go a week or two without another self-inflicted verbal catastrophe.

We keep hearing that the presidential election this year may come down to who has the better ground game, and perhaps it will if Mitt Romney can manage to go a week or two without another self-inflicted verbal catastrophe.

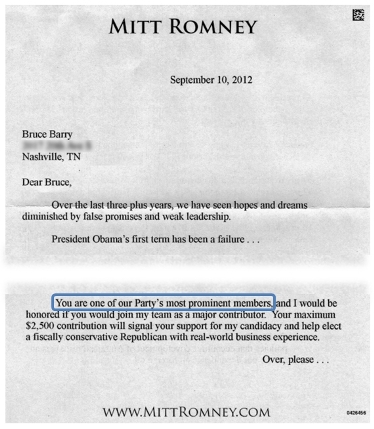

But what kind of effective ground game can the Romney campaign possibly be cultivating if they are sending a fund-raising letter to someone like me?

Public election records that campaigns mine to target contributors and voters show that I’ve been registered in the same county for over 20 years, vote in essentially every election, and have never voted in a Republican contest in our open primary system.

Granted, I’m just one schmoe in a state that doesn’t matter at all strategically. But if the Romney folks are dropping mail pieces on people like me, then supporters who actually give money to his campaign should be seriously concerned about how their dollars are being spent.

Defining the Middle Class

Posted: September 14, 2012 Filed under: Economics, Politics Leave a comment Arguments over what politicians mean when they say they want to help the “middle class” are almost as old as the existence of a middle class. And with both Mitt Romney and Barack Obama beating the middle class drum silly this political season, it was only a matter of time before a conversation about who is and isn’t in the middle class resurfaced.

Arguments over what politicians mean when they say they want to help the “middle class” are almost as old as the existence of a middle class. And with both Mitt Romney and Barack Obama beating the middle class drum silly this political season, it was only a matter of time before a conversation about who is and isn’t in the middle class resurfaced.

And so it did with Mitt Romney’s exchange with George Stephanopolous on ABC Friday morning:

MITT ROMNEY: Let me tell you, George, the fundamentals of my tax policy are these. Number one, reduce tax burdens on middle-income people. So no one can say my plan is going to raise taxes on middle-income people, because principle number one is keep the burden down on middle-income taxpayers.

GEORGE STEPHANOPOULOS: Is $100,000 middle income?

MITT ROMNEY: No, middle income is $200,000 to $250,000 and less.

As the Wall Street Journal‘s What Percent Are You calculator reveals, $200K puts you in the 94th percentile of tax-filing households, and $250K puts you in the 96th percentile. So to the extent that Romney believes that being middle class in 21st century America means being in the top 4-6 percent, he’s going to deserve the ridicule he has manage once again to self-inflict. Of course, Romney did say $200-250K “or less,” so presumably he doesn’t put the middle class household wage floor at $200K. Even he’s not that dim.

To be fair, some will point out that Barack Obama’s pledge to avoid raising taxes on the middle class, coupled with policy proposals that preserve tax cuts for those earning less than $250K, means that Obama also defines the middle class all the way up into the mid 200Ks. I’m not aware that Obama has been clumsy enough to make that upper bound explicit as a definitional matter in the way that Romney just did. And of course, any definition of middle class tied to raw income levels or earning percentiles is flawed by its failure to factor in vast geographic differences in cost of living, not to mention variations in household size and other relevant factors. As we all know, a given level of income goes a whole lot further for a childless couple in Nashville than for a family of four in San Francisco.

So where should we locate the middle class in household income terms? A recent Wall Street Journal Marketwatch piece blandly asserted that the middle class is comprised of “the 50% of American households earning between $39,000 to $118,000.” Using the Journal‘s calculator, that range runs from the 46th to the 84th percentile of tax filing households … and seems rather arbitrary.

We know from recent Pew survey data how many self-regard as middle class: Just under half of adults call themselves middle class, only a few percent less than said the same thing four years ago, with reasonably similar percentages saying this across gender and race divides.

If being middle class is essentially a state of mind, then one way to define a middle class income is to ask people where they would peg the number. The Pew survey gave that a shot, asking respondents to say how much annual income a family of four would need to lead a middle-class lifestyle. The overall median response to this question was $70K – a number not far off from the actual median income for a four-person household based on Census Bureau numbers ($68.2K) and well below the definition of middle class amidst the rarified air on Planet Mitt.

An alternative approach is to think about the key elements of consumption one’s income makes possible, or easy, or not so easy. I kind of like the version of this approach put forward by some guy named Eric commenting on a blog post about the Romney remark at The Atlantic:

You should define class by the ability to pay for two new cars, a $1200 mortgage (arbitrary for this comment), private schools (especially if you live in a city), a $3,000 health insurance deductible, and organic/sustainably produced foods. Then assume that most people pay for cable and cell service. Anyone who doesn’t worry about these things is above middle class. Anyone who must make trade-offs among them is in the middle. Anyone who cannot pay for any of these is poor.

We can quarrel about the organic food part, but otherwise it makes quite a bit of sense to me.

A version of this post appears on the Nashville Scene‘s Pith in the Wind blog.

Two Questions for Republicans

Posted: September 6, 2012 Filed under: Law, Politics Leave a comment My questions are catalyzed by Bill Clinton’s convention remarks about voter suppression and reaction to it. This is not a topic Clinton dwelled on, but he did say this:

My questions are catalyzed by Bill Clinton’s convention remarks about voter suppression and reaction to it. This is not a topic Clinton dwelled on, but he did say this:

If you want every American to vote and you think it’s wrong to change voting procedures just to reduce the turnout of younger, poorer, minority and disabled voters, you should support Barack Obama.

Responding over at National Review Online the next morning, veteran conservative pundit John Fund accused Clinton of “shamelessly playing the race card” with criticism that qualifies as “reckless and irresponsible.” Fund was especially galled by Clinton’s timing:

His timing in attacking efforts to combat voter fraud couldn’t have come at a more ironic time. Just yesterday, a Democratic state legislator in Clinton’s native Arkansas pled guilty along with his father, a West Memphis police officer, and a West Memphis city councilman to a conspiracy to commit voter fraud. Democratic representative Hudson Hallum was part of a conspiracy to bribe voters in three separate elections in 2011.

A quick read through the U.S. Attorney’s news release (pdf) announcing the charges and guilty pleas reveals some serious warp in Fund’s sense of irony. The charges were hardly the kind of imagined voter fraud that the recent spate of laws is supposed to combat in order to preserve the republic. These clowns in Arkansas helped absentee voters obtain and complete ballots, bribed them with food and hooch, collected the ballots in unsealed envelopes, looked at them, and then sealed and mailed only those who voted for Rep. Hallum. In other words, much that is felonious, but nothing that voter ID requirements or curtailed voting hours would halt.

So here are my two question for thoughtful GOPers:

First, when a venerable commentator like John Fund has to rely on a transparently irrelevant example of election fraud in order to justify these new laws, does that not reveal for all to see, as opponents of these laws have been claiming all along, that this is a solution in search of a (non-existent) problem?

And second, when Bill Clinton suggests that Republicans are tinkering with voting laws in a specifically calculated effort to “reduce the turnout of younger, poorer, minority and disabled voters,” can you honestly look yourself in the mirror and assert with genuine conviction that this is not precisely the intent (not just the effect, but the intent) of those pushing these laws?

A version of this post appears on the Nashville Scene‘s Pith in the Wind blog.

Campaign Consciousness and Governing Consciousness

Posted: August 24, 2012 Filed under: Politics 2 Comments I usually find Times columnist David Brooks’ faux-moderate conservativism to be more insipid than enlightening, but today’s column offers a trenchant (and perhaps even original) insight into what’s wrong with our campaign-driven politics. Noting that in Congress, Paul Ryan repeatedly shows himself unwilling to accept half-measures or compromise on fiscal matters or entitlements, Brooks accuses Ryan of choosing “political fantasy” over significant progress:

I usually find Times columnist David Brooks’ faux-moderate conservativism to be more insipid than enlightening, but today’s column offers a trenchant (and perhaps even original) insight into what’s wrong with our campaign-driven politics. Noting that in Congress, Paul Ryan repeatedly shows himself unwilling to accept half-measures or compromise on fiscal matters or entitlements, Brooks accuses Ryan of choosing “political fantasy” over significant progress:

Ryan was betting that three things would happen. First, he was betting that Republicans would beat President Obama. Second, he was betting that Republicans would win such overwhelming Congressional majorities that they would be able to push through measures Democrats hate. Third, he was betting that a group of Republican politicians would unilaterally slash one of the country’s most popular programs and that they would be able to sustain these cuts through the ensuing elections, in the face of ferocious and highly popular Democratic opposition …. Ryan’s fantasy happens to be the No. 1 political fantasy in America today, which has inebriated both parties. It is the fantasy that the other party will not exist. It is the fantasy that you are about to win a 1932-style victory that will render your opponents powerless.

The piece goes on to fashion a duality between “campaign consciousness” — the strident policy argument vibe one cultivates before an election — and “governing consciousness” — the mindset between election seasons that leads office holders to “navigate our divides to come up with something suboptimal but productive.” Brooks tags Ryan as good on the former but lousy on the latter.

Although Brooks confines his accusation to Ryan, influential figures in both parties exhibit this tendency, feeding the paralyzing gridlock that prevents anything from getting done in Congress even when it’s not campaign season. Brooks is right that way too much of the campaign discourse we endure rests on an absurdist assumption that winning the electoral college will magically activate a governing mandate. As if.

But even if there are Democrats mirroring Ryan’s behavior, it can also be said that Barack Obama has (suffers from?) the opposite profile — too much governing consciousness (an inclination to capitulate for marginal gain) and too little campaign consciousness. As Thomas Frank argues in an essay getting a lot of attention, overeager conciliation undermines your negotiating leverage, inviting the very rigidity on the other side that ends up undermining your conciliatory move.

A version of this post appears on the Nashville Scene‘s Pith in the Wind blog.

A Debate Debate in a Tennessee Congressional District

Posted: August 15, 2012 Filed under: Politics Leave a comment In Tennessee’s 4th Congressional District, incumbent Republican Rep. Scott DesJarlais is refusing to debate his Democratic opponent Eric Stewart on the (ostensible) grounds that Stewart isn’t running enough of an issues campaign to justify meeting on the same stage. DesJarlais’ campaign manager had this to say:

In Tennessee’s 4th Congressional District, incumbent Republican Rep. Scott DesJarlais is refusing to debate his Democratic opponent Eric Stewart on the (ostensible) grounds that Stewart isn’t running enough of an issues campaign to justify meeting on the same stage. DesJarlais’ campaign manager had this to say:

“Eric has yet to release a meaningful platform of any sort, even on his own website, and has placed the debate cart before the platform horse. We simply challenged him to actually articulate where he stands on key issues like taxes, energy, spending, the definition of marriage, and who he will be voting for in the presidential election.”

For an office holder with the advantage of incumbency, a large campaign finance edge and a reputation for articulateness that falls somewhere short of Aristotelian, ducking debates is hardly a novel or startling strategic move. Justifying the dodge as a response to an opponent’s supposedly thin platform is, I suppose, as good a way as any to avoid saying “I don’t want to debate him because it will only hurt me and I can win without doing it so piss off.”

Even so, the DesJarlais spokesman’s “even on his own website” charge is sufficiently concrete that it invites a little followup. Is it the case that Stewart fails to articulate positions on fundamental issues? The short answer is that the DesJarlais campaign claim is pretty much valid.

On the issues Stewart’s website is sketchy and shallow. It has only two issue categories. The first, on jobs and the economy, makes a few vague statements about business tax credits, overseas hiring by government contractors, ending “tax breaks to billionaires and big corporations” and rebuilding infrastructure, but offers no specific ideas or proposals. The other category, Social Security and Medicare, does assert that Stewart will “fight against any effort to privatize Social Security and work to defeat any legislation that tries to turn Medicare into a voucher program,” which does qualify as an issue-oriented pledge to oppose aspects of the so-called Ryan plan.

To be fair, DesJarlais’ website isn’t much more detailed, although it does cover more issues with its own half-baked pablum (healthcare, energy, immigration, abortion, marriage rights, the second amendment), and of course DesJarlais has a voting record in Congress, such as it is.

But is this unfair to Stewart? Do challengers commonly run issue-free campaigns, focusing exclusively on their incumbent-opponents’ records? For perspective I picked out a contested race with a similar dynamic: a serious Democratic challenger facing a freshman Republican incumbent. In Illinois’ 8th Congressional District, Republican Rep. Joe Walsh faces a challenge from Democrat Tammy Duckworth in a closely watched contest. And frankly, the issues page of the Duckworth campaign website makes Eric Stewart’s look minimalist in comparison. Duckworth offers separate pages with policy statements not just on the economy and entitlement programs as Stewart does, but also on fiscal policy, education, energy, national defense, Afghanistan, Israel, civil rights (including women’s rights and workers’ rights), and veteran’s issues. And her statements on most of these issues are quite specific — identifying concrete priorities, and naming bills and programs she supports and opposes.

Stewart doesn’t help himself with this response to the incumbent’s debate avoidance: “Scott DesJarlais wants to talk about votes I might cast in the future. I want to talk about votes he’s cast in the past.” Yes, we get it, you are trying to unseat an incumbent by directing voter attention to his views and votes — that’s the challenger’s task. But to suggest that “votes I might cast in the future” are somehow a distraction from the real business of a political campaign is daft.

None of this is to excuse DesJarlais’ lame efforts to avoid debates. There is no good reason to not debate a legitimate major party opponent. But his stated reason for the dodge — that his opponent has yet to articulate serious positions on many issues — does appear to have some truth to it. Of course, that’s precisely a reason to have a debate, not a justification for avoiding one.

A version of this post appears on the Nashville Scene‘s Pith in the Wind blog.